This condition involving the immune system attacking the thyroid gland now affects at least 14 million Americans and up to 7.5 percent of people globally.

What Are the Symptoms and Early Signs of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

- Goiter symptoms (an enlarged neck and disappearance of necklines)

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Neck pain or swelling

- Throat discomfort

- Voice changes

- Difficulty swallowing

- Difficult or labored breathing

Systemic symptoms can vary depending on thyroid function but include the following:

- Cold or heat intolerance

- Hair loss or thinning

- Infertility

- Irregular or heavy periods and irregular ovulation

- Fatigue

- Disturbed sleep

- Puffy face

- Weight gain or loss

- Memory problems; depression; trouble concentrating

- Increased resistance in blood vessels

- Decreased heat production and decreased fat breakdown

- Poor gallbladder function; gallstones

- Slow heart rate; decreased heart pumping ability; fluid around the heart; reduced blood flow

- Constipation; sluggish digestion

- Decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in kidneys; reduced water excretion

- Decreased liver function; increased total cholesterol; low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and lipoprotein(a)

- Slow breathing; low oxygen levels; fluid buildup around the lungs

- Decreased muscle strength and reflexes; muscle or joint pain; cramps

- Dry, cold, yellowish, thickened skin

What Causes Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

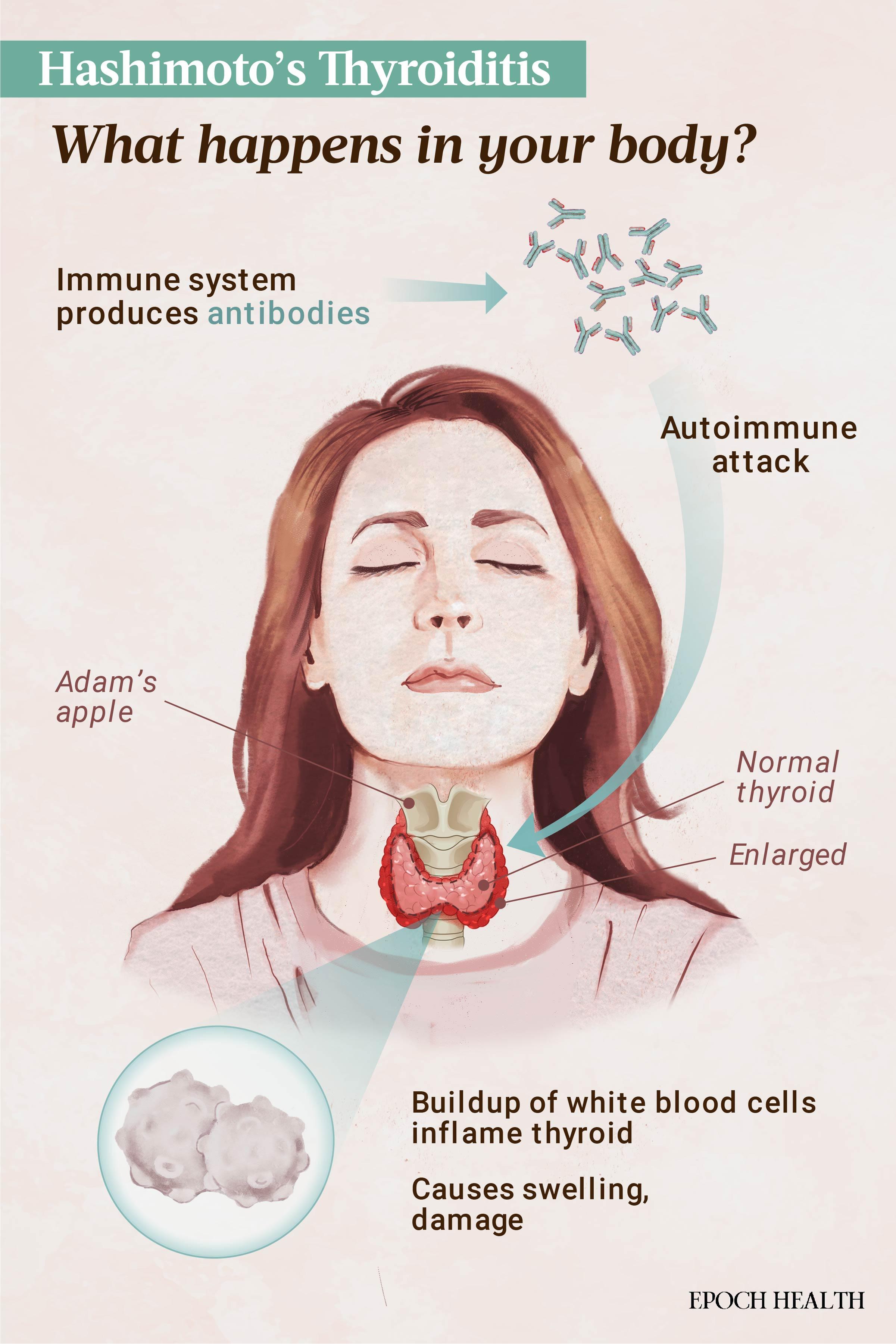

The thyroid has many functions, including regulating growth and development, energy, body temperature, heart rate, and the rate of metabolism. In HT, an immune imbalance prompts an immune response, disrupting these functions. Antibodies against thyroid-specific proteins such as thyroid peroxidase (TPO) and thyroglobulin (TG) are produced, resulting in damage to the thyroid. This triggers inflammation and infiltration of the thyroid by immune cells called lymphocytes, leading to a seemingly endless cycle of damage and inflammation.

Over time, this cycle can lead to fibrosis, or scarring, in the thyroid. This impairs the thyroid’s ability to produce hormones, resulting in hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid function.

Factors

The key factors thought to play a role in HT’s development include:

- Genetics and epigenetics: Genetic predispositions, together with epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation, can significantly influence the risk of developing HT. This combination likely accounts for more than half of the susceptibility to HT.

- Infections: Links have been observed between HT and various bacterial and viral infections, including chronic hepatitis C, H. pylori, T. gondii, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes virus, SARS-CoV-2, Y. enterocolitica, B. burgdorferi (which can cause Lyme disease), Hantavirus, and Saccharomyces. Gut bacterial imbalances might also contribute to HT development.

- Stress: Stress affects multiple systems, including the gut, nervous, immune, and endocrine systems. These stress-induced changes can trigger inflammation and may contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases like HT in genetically predisposed individuals.

- Oxidative stress: Some free radicals—byproducts of processes like digestion—are normal, but they become problematic when they outnumber antioxidants. In HT, research shows an excess of free radicals that can damage thyroid cells and trigger an immune attack. Studies have identified elevated oxidative stress markers and reduced antioxidant levels in individuals with HT.

- Toxin exposures: Exposure to substances such as mercury, nitrates, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), organochlorine pesticides, and flame retardants can disrupt thyroid function and immune regulation, potentially triggering HT. Bisphenol A (BPA), in particular, has been linked to thyroid autoimmunity, lower thyroid hormone levels, and higher thyroid antibody levels, as well as disruptions to thyroid hormone receptors. Further research is needed to further understand the exact impact on thyroid function.

- Nutritional and dietary factors: Dietary imbalances like excessive iodine, along with deficiencies in iron, selenium, and vitamin D, are associated with HT. Interestingly, moderate alcohol consumption may offer some protective effects.

- Hormones: The interplay of sex hormones and pregnancy can activate autoimmune genes, influencing HT development. Progesterone, particularly after childbirth, may also contribute to thyroiditis.

- Microbiome: Alterations in gut microbiota, including harmful microbiota such as Bacteroides fragilis and reductions in beneficial Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, have been noted in HT patients. However, a direct causal association has not been established.

- Radiation exposure: Long-term or repeated exposure to radiation increases the risk of autoimmune thyroid diseases.

- Drugs: Certain medications that modulate the immune system increase the risk of developing HT. These include interferon-alpha, used to treat conditions like hepatitis and cancer; amiodarone, a heart medication; lithium, a treatment for bipolar disorder; alemtuzumab, used to treat multiple sclerosis; PD-1/PD ligand-1 axis inhibitors, a class of cancer immunotherapies.

What Are the Types of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

The other autoimmune thyroid condition is Graves’ disease, which involves the formation of autoantibodies against the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor. Graves’ disease leads to hyperthyroidism, or overactive thyroid function.

- Painless thyroiditis: Also called silent or lymphocytic thyroiditis, this variant involves thyroid inflammation without pain or tenderness.

- Painful thyroiditis: In this variant, the thyroid gland becomes swollen and painful, often accompanied by fever. It is also called subacute thyroiditis or De Quervain thyroiditis.

- Postpartum thyroiditis: This temporary form of thyroiditis can occur in women within the first year after giving birth. It may cause fluctuating levels of thyroid hormones, leading to periods of both hyper- and hypothyroidism, but it usually resolves on its own. If it persists, it is classified as Hashimoto’s.

- IgG4-related thyroiditis: This is a recently identified variant that can mimic other thyroid disorders and is characterized by the presence of IgG4 antibodies. It is considered systemic.

- Fibrous variant: Occurring in about 10 percent of HT cases, this variant is marked by extensive fibrosis replacing normal, functional thyroid tissue.

- Fibrotic and atrophic variant: This variant is characterized by extensive fibrosis and atrophy of the thyroid gland.

- Riedel thyroiditis: This is a rare, chronic, and progressively worsening form of thyroiditis marked by significant fibrosis that may spread beyond the thyroid gland, potentially compressing nearby structures. While its link to HT isn’t well understood, some researchers view it as a variant.

- Hashitoxicosis: In this type, thyroid hormones are released from damaged thyroid follicles, causing temporary periods of thyrotoxicosis from too much thyroid hormone. Typically, this condition is managed with beta blockers instead of levothyroxine and usually progresses to permanent hypothyroidism within three to 24 months.

Who Is at Risk of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

- Age: HT can occur at any age, including childhood and adolescence. However, it typically affects women between the ages of 30 and 50.

- Sex: The risk of developing HT is at least four times greater for women than men. Additionally, thyroiditis can occur after giving birth. About 20 percent of women who develop postpartum thyroiditis eventually develop HT.

- Children with genetic syndromes: Although HT is less common in children than adults, children with genetic conditions such as Turner syndrome, Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, and 22Q11DS have an increased risk. Due to this heightened risk, regular screening and monitoring for HT in these children is recommended.

- Ethnicity: Although anyone can get HT, it is diagnosed most often in those of European descent.

- Socioeconomic level: Research indicates that people in low- to middle-income areas are at a higher risk of developing HT thyroiditis. Interestingly, the prevalence is also higher in high-income areas compared to upper-middle-income areas.

- Family history: Having a family member with HT increases the likelihood of developing it. The risk is almost 17 times higher in siblings.

- Obesity: Research indicates that obesity can increase the risk of developing HT and is linked to higher thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAbs) levels. Additionally, gaining weight in childhood has been connected to a higher chance of developing thyroid autoimmunity and hypothyroidism later in life.

- Autoimmunity: Patients diagnosed with other autoimmune conditions are more likely to develop HT.

How Is Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Diagnosed?

- Clinical assessment: Doctors begin by reviewing symptoms and medical history and physically examining the thyroid gland. A goiter may be firm and enlarged, while atrophy or fibrosis renders the thyroid inaccessible.

- Blood tests: These measure thyroid hormone levels (TSH, fT4, fT3) and thyroid-specific antibodies (TPOAbs and TGAbs). It is important to note that while TPOAbs are commonly present, only TGAbs may be present in about 5 percent of cases.

- Ultrasound imaging: This may be performed to detect any enlargement, patchy or uneven textures, abnormally dense tissue, or small nodules in the thyroid.

- Fine needle aspiration (FNA): This is a minimally invasive way to obtain a sample of tissue or biopsy from the thyroid using a fine needle. The sample can then be evaluated for lymphocytic infiltration to diagnose HT. In the case of a thyroid nodule or any abnormal lymph nodes, the sample would be examined for benign or cancerous properties.

It is important to note that HT thyroiditis does not always present as hypothyroidism with elevated TSH. Other presentations include:

- Hashitoxicosis: Periods of hyperthyroidism (low TSH, high fT4) may occur initially before progressing to hypothyroidism.

- Euthyroidism: This exhibits normal TSH and T4 levels but with TPOAbs and typical ultrasound features.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism: TSH is elevated, but fT4 and fT3 are normal.

- Overt hypothyroidism: TSH is elevated, but fT4 is low.

If TSH is the only biomarker measured, this variability could result in delayed diagnosis and advanced tissue damage. Thus, comprehensive testing, which includes measuring free T4 and thyroid antibodies, is necessary to assess thyroid status and monitor HT progression accurately.

Functional Medicine Approach

Practitioners in this field might recommend a more extensive set of tests to uncover underlying autoimmune triggers and imbalances. These tests include:

- Full thyroid panel measures TSH, total T4, free T4, total T3, free T3, reverse T3, and thyroid antibodies (TPOAbs and TGAbs) to evaluate thyroid metabolism and possible conversion issues.

- Hormonal assessment tests hormones like cortisol to assess overall hormonal balance and adrenal function.

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential helps understand general health and immune status.

- Nutritional testing assesses levels of crucial nutrients such as selenium, iodine, iron, zinc, vitamin D, and fatty acids.

- Stool testing evaluates gut health and microbiome status to help understand autoimmune triggers and provide insights into inflammation.

- Food sensitivity testing identifies potential food triggers that can cause immune reactions and inflammation. Alternatively, an elimination diet may be recommended.

- Toxic exposure screening checks for harmful exposures that could influence thyroid and immune function.

What Are the Complications of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

- Increased cancer risk: While not all researchers agree, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis determined that individuals with HT may face a higher risk of certain cancers and should, therefore, undergo regular screenings. The types of cancer associated with HT include thyroid, breast, lung, digestive system, urogenital, and blood cancers, as well as prolactinoma, a benign tumor of the pituitary gland.

- Pregnancy risks: Even with optimal levothyroxine supplementation, some—but not all—studies have found women with TPOAbs or TGAbs to have a higher risk of in vitro fertilization failure, miscarriage, and preterm birth. Proactive management of thyroid health before and during pregnancy is crucial.

- Cognitive decline: The chronic inflammation and autoimmune processes in HT may contribute to cognitive impairment and accelerated brain aging over time.

- Metabolic disorders: Research has linked HT with an increased risk of developing certain metabolic health issues, such as insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions. These include increased blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol levels that occur together, increasing your risk of heart disease, stroke, and Type 2 diabetes.

- Adverse cardiovascular outcomes: HT has been linked to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, and congestive heart failure.

- Myxedema coma: Untreated hypothyroidism, a possible outcome of HT, can progress to myxedema coma, a rare but life-threatening condition. This extreme endocrine emergency requires immediate treatment in an intensive care unit. Myxedema coma typically affects individuals over 60, predominantly women, occurring almost exclusively in the winter months. It is characterized by severe metabolic slowing, which leads to profound lethargy, hypothermia, and other critical symptoms that necessitate urgent medical intervention.

- Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy, a rare but serious neurological condition, is also known as steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT). It is characterized by symptoms such as confusion, stroke-like episodes, and seizures. The condition is likely due to complex immune system responses that extend beyond the thyroid.

What Are the Treatments for Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

High levels of TSH can be associated with health issues like poor heart health and metabolic problems, and low levels can lead to lower bone density and a higher risk of fractures. Therefore, the dosage of levothyroxine must be carefully adjusted, which is done through regular monitoring of TSH levels, usually every six to eight weeks after any dosage change.

Although levothyroxine (synthetic T4) is the conventional treatment for HT, it might not be the best option for everyone. Some patients may find that alternative thyroid medications offer improved symptom relief and better overall health outcomes.

- Natural desiccated thyroid (NDT): One alternative is natural desiccated thyroid (NDT) medication, such as Armour Thyroid or Nature-Throid. These medications are derived from the dried thyroid glands of pigs and contain a combination of the thyroid hormones T4 and T3. Some patients report experiencing improved symptoms and better quality of life when switching from levothyroxine to an NDT medication. This may be due to the presence of both T4 and T3 hormones, which more closely mimic the natural thyroid hormone balance. NDT medications are not approved by the FDA because the thyroid hormone content can vary between batches.

- Combination T4 and T3 therapy: Another alternative is the combination of synthetic T4 (levothyroxine) and synthetic T3 (liothyronine) hormones. This approach may benefit individuals who do not achieve optimal symptom relief with T4 (levothyroxine) medication alone. Adding T3 can help address the conversion issues some HT patients experience, where the body struggles to convert T4 into the active T3 hormone.

- Compounded bioidentical hormones: Some health care providers may recommend compounded bioidentical thyroid hormone medications for HT patients. These custom-formulated preparations aim to match the body’s natural thyroid hormone profile more closely. Compounded bioidentical hormones can include T4, T3, and even T2 and T1 thyroid hormones. This personalized approach may help those who have not found relief with standard thyroid medications.

- Surgery: In more severe cases, such as when there is aggressive compression in the neck, the coexistence of cancer nodules, or persistently high TPOAbs affecting quality of life, a thyroidectomy to remove the thyroid surgically may be deemed necessary. Potential complications of thyroidectomy include damage to the laryngeal nerve, hypocalcemia (low calcium levels), and Horner’s syndrome (a neurological condition affecting the eye).

What Are the Natural Approaches to Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

1. Diet

The scientific landscape can be a bit murky when it comes to managing HT through diet. While some studies have suggested the benefits of specific dietary approaches, such as the autoimmune protocol (AIP) or gluten-free diet, not all studies agree. Nutrition science is notoriously difficult to control, and the study duration and quality of the food consumed can significantly affect results.

The consistent message in reviews of the research is that the results are mixed. Researchers agree that an anti-inflammatory diet is necessary and that pro-inflammatory saturated fats, sweets, and refined carbs should be restricted. However, they are still searching for that “one” elusive diet that works for Hashimoto’s. The reality is that what causes inflammation and immune reactions varies by individual.

Elimination Diet

Elimination diets involve temporarily omitting certain foods to allow the immune system to calm down and then reintroducing foods one by one to identify potential triggers. The diet can be used in conjunction with food sensitivity testing or as a food sensitivity test in and of itself. Typical elimination diets for autoimmune conditions eliminate the most common food allergens (wheat, milk, soy, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, and peanuts) and foods you already know cause you to react. It may also exclude other or all grains, nightshade vegetables, legumes, sugar, and processed foods.

Autoimmune Protocol (AIP) Diet

The AIP diet is a popular dietary approach that has shown promise in managing autoimmune conditions like HT. This elimination-style diet focuses on reducing inflammation and supporting gut health, with the goal of re-modulating the immune system.

- Dairy products

- Grains (especially gluten-containing grains)

- Nightshade vegetables

- Legumes (including beans, peas, and lentils)

- Eggs

- Nuts and seeds

- Processed foods

- Refined sugars

- Coffee

- Alcohol

The rationale behind the AIP diet is that these foods can trigger inflammation and immune reactions in susceptible individuals, potentially exacerbating autoimmune conditions like HT. For example, nightshade vegetables contain alkaloids that may contribute to inflammation in some people.

Gluten-Free Diet

A gluten-free diet is commonly suggested for Hashimoto’s patients because gluten can increase intestinal zonulin, a protein that regulates tight junctions, leading to increased intestinal permeability. This condition allows particles and toxins to enter the bloodstream, potentially sparking an inflammatory immune response.

2. Targeted Supplementation

Due to the complex nature of interactions between the gut-brain axis, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis, and gut-thyroid axis, supplementation needs can vary greatly from one individual to another. Common nutrients that might support the overall health of those with HT include those that promote gut health, aid in balancing the microbiome, support neurotransmitter function, regulate blood sugar, enhance insulin sensitivity, support adrenal health, and modulate immune system activity. For example, myo-inositol, a type of B vitamin-like substance, has been studied for its possible role in supporting thyroid function by influencing insulin sensitivity and hormone signaling, making it a potentially valuable addition for some individuals with HT.

- Vitamin D

- Antioxidants

- Omega-3 fatty acids

- Magnesium

- Zinc

- Selenium

However, given the specificity required in choosing the right supplements, it is crucial to consult a health care practitioner who specializes in autoimmune disorders and is knowledgeable about supplementation.

3. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

A recent systematic review and network meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials found that herbal medicine may be beneficial as a complementary or alternative treatment for HT. The review consistently found that certain herbal formulas effectively reduced thyroid antibody levels and improved clinical symptoms without any serious adverse effects reported.

How Does Mindset Affect Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

Moreover, chronic stress can alter the gut’s good bacteria, reducing their diversity and the production of anti-inflammatory substances. It can even cause genetic changes that might affect your immune system and be passed down to future generations.

How Can I Prevent Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis?

- Maintain an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant-rich, and nutrient-dense diet that works for you.

- Work with a professional to identify and address any nutritional deficiencies or insufficiencies and maintain healthy nutrient levels through diet or supplementation.

- Nurture a healthy gut by addressing intestinal permeability and promoting a balanced microbiome.

- Practice good oral health; more plaque may increase your risk of autoimmunity.

- Try to get at least seven hours of restorative sleep each night.

- Manage stress and support mental health.

- Avoid or reduce exposure to toxic substances such as chemicals, pollutants, and radiation.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Exercise regularly, including both moderate aerobic and weight-bearing activity.

- Be proactive in your own care and keep up with regular checkups and monitoring. Ensure you have a health care team that works well together to meet your needs.